Human Microbiome Project is expected to trigger many new molecular diagnostic assays

Meet the human microbiome, considered by some medical researchers to be the newest biomedical frontier. A major effort to map the human microbiome is expected to identify a significant number of new biomarkers that will be useful in both clinical pathology diagnostic tests and therapeutic drug development.

Known as the Human Microbiome Project, the five-year program is funded with $115 million in grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Researchers are well on their way to produce a comprehensive inventory of microbes—bacteria, viruses, yeast and fungi—that live in or on the human body, along with information about their role in disease development or prevention. The overall goal of this international effort is to identify which microbes are harmful and figure out ways to prevent or treat diseases they cause.

“This could be the basis of a whole new way of looking at disease,” stated Margaret McFall-Ngai, Ph.D., a researcher at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in an article in Science Daily. “In order to understand how changes in normal bacterial populations affect or are affected by disease, we first have to establish what normal is or if normal even exists.”

Researchers have long suspected and researched the beneficial role microorganisms play in human health. However, recent advances in molecular technology make it faster and cheaper for scientists to accurately identify and characterize all the species that make up an individual’s microbiome.

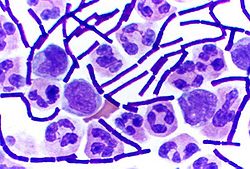

Studies indicate that humans live in a symbiotic relationship with most microbes, which are harmless or necessary to life and health. Some, however, are blamed for digestive disorders, skin diseases, gum disease, obesity, autism and cancer.

Scientists estimate that trillions of microorganisms inhabit the average healthy human and outnumber human cells 10 to one. In fact, human skin is literally crawling with trillions of single-celled critters. By itself, the human gut harbors 100 trillion microorganisms!

However, the type and number of different microbial species vary from person to person, noted Martin Jack Blaser, M.D., a researcher at New York University. He is exploring the role bacteria play in skin diseases. Blaser told Science Daily that he believes an individual’s bacterial signature may be as unique as their DNA signature or fingerprint.

Bacteria form tiny colonies that settle in different areas of the body, similar to ecosystems formed by plants and animals on Earth, noted Jeffrey Gordon, M.D., a microbiologist at the University of Washington in St. Louis, in a recent article published by McClatchy Washington Bureau. Different tribes of microbes are associated with different maladies. For example, bacteria associated with psoriasis favor the outer elbow and eczema bugs prefer the inner elbow.

A study at the University of Colorado, Boulder, is exploring the role bacterial communities in the human digestive tract may play in inflammatory bowel diseases. The researchers are comparing microbial communities in samples from people with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis with healthy volunteers to see how they might change in relation to disease.

Researchers at the University of Washington in St. Louis have discovered that obesity is associated with changes in number of certain bacteria in the digestive tract. A study from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine identified 383 microbial genes that differ significantly between pairs of obese and slender twins. Lead researcher Matthias Tschöp, M.D., reported in the journal Nature that microbes in obese people harvest sugars and fats in diet more efficiently than they do in slender people.

McFall-Ngai suggests that the overwhelming number of microbes and their potential role in health and disease make it possible that knowledge of the human microbiome may turn out to be as important—or more important—to the understanding human health than the human genome. “With the complexity of the system,” she added, “it is definitely going to be more difficult [than mapping the human genome].”

Pathologists and clinical laboratory managers can expect the map of the human microbiome to be the source of a host of new laboratory tests. The example of testing for C. pylori to diagnose peptic ulcers is a well-established example.

Related Information:

Germ phobes can’t win: We’re all host to trillions of microbes