Critics of an inquiry into histopathology errors at the Royal Bristol Infirmary argue that as many as 6,800 cases over eight year may have errors in diagnosis

In Bristol, England, the issue of serious errors in the anatomic pathology service of the Bristol Royal Infirmary (BRI) during the years 2000 to 2008 refuses to go away. Earlier this year, critics of an inquiry commissioned by the parent health trust became vocal once again after public notice was given of plans to consolidate histopathology services in the region.

These critics continue to be upset about how the inquiry into ongoing problems with the anatomic pathology service at BRI was conducted during 2009 and 2010. Newspapers in the United Kingdom have given the story wide play. Stories were published about pathology errors at BRI and the public learned about the misdiagnoses of specific cancer patients whose names became known.

Useful Lessons for Pathologists and Clinical Laboratory Managers

For pathologists and clinical laboratory managers in all developed countries, this still-unfolding story is a reminder of why it is essential that there be public trust in the accuracy and integrity of medical laboratory testing. Not only is the accuracy of the pathology testing important—but investigations into claims of errors and patient harm should be conducted with full public engagement and transparency.

That is why, in Bristol, public criticism about the lack of transparency by the health authorities tasked with investigating claims of ongoing errors in histopathology testing is one reason this story continues to resurface and attract media attention across the United Kingdom.

The basic facts are these:

- On multiple occasions from 2000 through 2009, physicians in Bristol raised concerns about what The Sunday Telegraph described as “repeated and critical blunders” happening within the anatomic pathology laboratory at the Bristol Royal Infirmary.

- The Sunday Telegraph also wrote that “submissions by specialist doctors said other serious errors [in pathology diagnoses] had caused the death of a child, while other patients were treated for the wrong disease, received a late diagnosis, or were given needless toxic treatment.”

- Among the patients who were affected by these errors was Jane Hopes. She was a 55-year old senior manager at the Bristol Royal Infirmary. In 2001, she had a breast biopsy which, at that time, was diagnosed as benign. Three years later, at the age of 55, Hopes died from breast cancer. Before her death, she learned about the error in the diagnosis of her biopsy specimen.

- On June 10, 2009, the British publication Private Eye published a story that described the ongoing problems within the histopathology department at the Royal British Infirmary. Dark Daily readers interested in the whistleblower aspects of this affair can read the original news story published by Private Eye. It was reproduced on page 203 of the inquiry that was conducted by the NHS.

- The University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust (UHBT) conducted an inquiry into the matter of histopathology errors at the Royal Bristol Infirmary. The findings of the inquiry were made public in December 2010. The 248-page inquiry report is accessible on the UHBT website for any pathologists interested in reading a detailed account of the events between 2000 and 2009.

- The inquiry had 26 histopathology cases reviewed by outside experts. Further, an outside audit was conducted of “3,500 cases randomly selected from histopathology specimens reported at UHBT in 2007.”

- The inquiry findings were that “no evidence could be found that the overall service was not safe.”

- Criticisms of the inquiry were immediate. Cancer patients who were known to have received an inaccurate diagnosis had not been given the opportunity to testify during the inquiry. The inquiry process was not transparent to the public.

- Another criticism addressed how pathology cases were selected for review, how these cases were assessed, and what criteria were used to evaluate the accuracy of the original diagnosis. Independent physicians reviewed the 26 cases where allegations of misdiagnosis had been made. Questions were raised about the audit of the other 3,500 cases and how to interpret the statements of the individuals who conducted the audit.

People concerned about this matter created an advocacy group called the South West Whistleblowers Health Action Group (SWWHAG). On its website, the group lays out its detailed criticisms of the inquiry and the manner in which it was conducted.

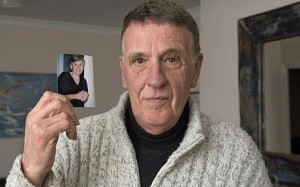

It was big news in Bristol, England, back in 2009 when newspapers learned of allegations of misdiagnoses and errors in histopathology testing at the Royal Bristol Infirmary. Newspaper reporters did stories about individual patients whose biopsies had been misdiagnosed. One such patient was Jane Hopes, who was employed as a senior manager at the Royal Bristol Infirmary. In 2001, her breast biopsy was reported as benign. She died three years later from breast cancer, having learned, before her death, of the missed diagnosis in her pathology report. Pictured above is Neal Willshaw, brother of Jane Hopes, from a photograph published in 2010. That was when the local hospital trust published its inquiry report about histopathology issues at the Royal Bristol Infirmary. (photo copyright The Sunday Telelgraph.)

For example, SWWHAG observes that the inquiry audited 3,500 histopathology cases and a rate of diagnostic error was identified. Given the 20,000 histopathology cases performed annually at the Bristol Royal Infirmary, SWWHAG asserts that, applying the audit rate of diagnostic error to that larger number of cases would indicate that the true rate of histopathology errors could involve as many as 6,800 patients between 2000 and 2009.

The point here is not to challenge the inquiry findings commissioned by University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust (UHBT), which operates the Bristol Royal Infirmary. Rather, it is to emphasize the ongoing and long-term consequences to UHBT—and anatomic pathologists practicing in Bristol—of public attitudes in response to this affair.

Questions about the Accuracy of the Anatomic Pathology Service

It is instructive that the National Health Service (NHS) continues to deal with the backlash from the claims that—for a period lasting as long as nine years—health authorities in Bristol failed to respond to repeated complaints of unacceptable errors in histopathology testing by physicians practicing in the community. It is now the third year since UHBT announced that an inquiry would take place and the media continues to publish stories about the criticisms of how this situation has been addressed.

The inquiry findings were published in December 2010. Yet, now, 15 months later, national newspapers still write stories about the community dissatisfaction with both the process of the inquiry and the findings of the inquiry.

The message to pathologists, pathology practice administrators, and clinical laboratory managers is clear. Maintaining public trust in the accuracy and the integrity of clinical laboratory and anatomic pathology testing is essential.

As long-time readers of Dark Daily know, it is always patients who pay the ultimate price for misdiagnoses of specimens and errors in laboratory testing. It is instructive in the case of the Royal Bristol Infirmary that, over the years 2000 to 2009, attending physicians who noticed inconsistencies in the histopathology reports for certain of their patients did make an effort to call attention to the situation.

For pathologists and medical laboratory scientists in their respective hospitals, this would be quickly recognized as a “red flag.” After all, it is surgeons who are first to compare the actual tissue viewed during surgery with the pathology report that was based on the earlier pathological examination of the patient’s biopsy specimen. In the United States and Canada, there are many examples where it is the surgeons who are first to call attention to pathology errors that caused patients to undergo unnecessary and life-changing surgeries.

What is important to both patients and the wider public living in these communities is how the healthcare system responds to news of errors or misdiagnoses in surgical pathology and clinical laboratory testing that has harmed patients. If the health authorities in Bristol, England, are still dealing with the consequences of negative publicity about long-standing problems in histopathology within the city, that is a sign that public engagement and full transparency during the review process fell short of public expectations.

In other developed nations, pathology errors and misdiagnoses have been discovered and generated wide media coverage in the communities where these problems took place. Each of these unfortunate situations provides a learning opportunity for the pathology profession, because it is the response to public disclosure of pathology misdiagnoses and patient harm which determines if the public will continue to trust the integrity of the medical laboratories that serve them.

Related Information:

The Independent Inquiry into Histopathology Services at Bristol Royal Infirmary, December 2010

Bristol cancer scandal: We were lied to, say victims

Inquiry into fears of botched cancer diagnoses

No action against doctors at centre of alleged cases of misdiagnosis

Hospital at centre of cancer misdiagnosis scandals makes secret payouts to patients