Pathology departments may want to create similar courses to teach medical students how to interpret genetic and genotyping tests

Genetic testing of participating university students was part of a special class that was conducted at the Stanford University School of Medicine last summer. The genetic pathology test was voluntary for the 54 students who participated in the eight-week course that was designed by a student.

The genotyping happened as part of the class, titled “Genetics-210, Genomics and Personalized Medicine.” It was intended to help medical students learn how to interpret genetic tests, and also to help them gain an understanding of ho learning the results of such tests could affect future patients.

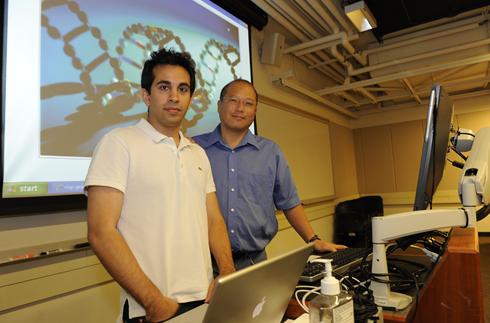

Keyan Salari, a sixth-year M.D./Ph.D. student, and faculty advisor Stuart Kim, Ph.D., Professor of Developmental Biology and of Genetics, developed the course.

(Keyan Salari, 6th-year M.D./Ph.D. Stanford University student, and Stuart Kim, Ph.D., Professor of Developmental Biology and of Genetics. Sourced from USA Today.)

Predictable Controversy Over Use of Genetic Testing at Colleges

In California, genetic testing of college students has been a controversial topic. Earlier in 2010, the California Legislature unsuccessfully attempted to stop the University of California Berkeley from providing mail-in genetic testing kits, also known as Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) tests, to all incoming freshman and transfer students as part of an orientation toward understanding personalized medicine.

That was not the case for this Stanford course, however. Only graduate and medical students had the option to undergo the commercial genetic testing. They then used the results as course materials for the class. Students provided their DNA/RNA though saliva samples that they mailed in test tubes to commercial labs Navigenics and 23andMe, who provided the genetic testing at a reduced educational rate. Students were required to pay a $99 co-pay.

Predictably, some quickly spoke out about the welfare and reactions of the students as they learned the results of their own genetic test.

“The concerns did not revolve around whether students should be taught about genetic testing—everyone agreed about that,” said Gilbert Chu, M.D., Ph.D., and a Stanford Professor of Medicine and Biochemistry, in a Scientific American article. “The concerns surround[ed] allowing students to undergo genetic tests themselves.”

Other considerations included whether the students would feel pressured to take the genetic tests, and how the university would be allowed to use the personal genetic data.

In response, the university delayed implementation of the course while a task force comprised of basic science faculty, clinical faculty, bioethicists, education officials and students debated the ethics, risks and merits of allowing the students to test themselves for genetic abnormalities.

“The task force really got into a philosophy-of-life debate,” said Dr. Kim in a San Francisco Chronicle article. “I’d want to know if I’m likely to get diabetes or cancer, because those can be prevented or treated early. But other people think the stress of knowing that would be too terrible.”

“Those of us who take care of patients understand that different people react to information differently,” said Dr. Chu, in an Inside Stanford Medicine article on the Stanford University website. “Some people focus on things that could go wrong to the point that it might affect their lives.”

As a result of the task force, Stanford University implemented precautionary measures that included:

- “Offering the course as an elective,

- “Making the genetic testing optional for those enrolled in the course,

- “Ensuring that students receive adequate baseline education prior to deciding whether to have the genotyping done,

- “Giving students the option of using either their own data or publicly available genome data for the classroom exercises, with instructors ‘blinded’ as to which type of data individual students are using,

- “Making counseling easily available to any student seeking advice or support.”

Genetic Testing is Here and Physicians Need to be Adequately Prepared

“When individuals want expert advice on their genetic test results they are going to turn to physicians or professors,” said Keyan Salari, the Stanford student who originated the course, and who is now the course director, in the same Scientific American article. “So it’s particularly important for these individuals to be adequately prepared.”

“Personalized medicine based on a person’s genetics is going to be a big part of the future of medicine,” Salari said in the San Francisco Chronicle article. “Friends of mine who are already physicians get patients coming into their offices with genetic printouts they’ve purchased, and my friends don’t know what to do.”

The fact that genetic testing and counseling has become part of two major medical university’s curriculums is another strong indicator that genetic testing will be a core component of diagnostic medicine in the very near future. Clinical laboratories and anatomic pathologists no doubt will soon see a marked increase in physician requests for genetics tests.

—Michael McBride

Related Information:

Medical School to Offer Course That Gives Students Option of Studying Their Own Genotype Data

Test Questions: Consumer Genomics Enters the Classroom

Is a DNA Scan a Medical Test or Just Informational? Views Differ

The Human Genome: Big Advances, Many Questions: USA TODAY

California Legislators’ Effort to Prevent Student DNA Testing Could Come Too Late