Inexpensive packing material pops up as an alternative to high-cost glass lab equipment for simple diagnostic tests, a potential boon in developing nations

By turning Bubble Wrap into a cheap alternative to glass test tubes and culture dishes, Harvard University scientists may have found a way to cushion clinical laboratories in developing countries from the high cost of basic lab gear.

This latest discovery is significant because it adds to the growing number of in vitro diagnostic testing systems that potentially can generate results as accurate as those produced in today’s state-of-the-art medical laboratories, but at a much lower cost.

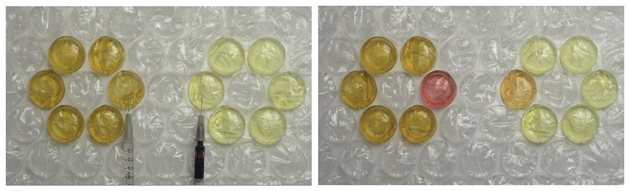

A color-based test for nitrite in drinking water (left syringe) and hemoglobin (right syringe) was developed using Bubble Wrap. (Photo and caption copyright Chemistry World.)

Second Cost-cutting Lab Prototype to Come Out of Wyss Institute

The previous prototype to come out of Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering wyss.harvard.edu was an Ebola test that employed an inexpensive paper-based diagnostic platform. Dark Daily reported on the Wyss Institute’s innovation in May.

The Harvard research team’s most recent success involved repurposing Bubble Wrap to serve as containers for storing liquid samples and for performing bio-analyses. They injected liquids into the sterile, air-filled pockets of Bubble Wrap with syringes and sealed the holes with nail polish hardener. Using this technique, they were able to conduct blood tests for anemia and diabetes, culture E. coli, grow Caenorhabditis elegans nematode worms and measure ferrocyanide electrochemically, all within the bubbles. The results of their study were published in the American Chemical Society’s journal Analytical Chemistry last year.

George Whitesides, Ph.D. at the Wyss Institute told National Public Radio’s (NPR) global health blog Goats and Soda that he began seeking an inexpensive alternative to glass when visiting developing countries and noticing that many medical laboratories did not have even simple equipment such as test tubes for running blood tests, storing urine samples or growing microbes.

George Whitesides, Ph.D., of Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, believes Bubble Wrap could be an inexpensive replacement for glass test tubes and culture dishes, a concept that would offer numerous benefits to pathologists and clinical laboratory scientists in poorer countries. “You can take out a roll of Bubble Wrap, and you have a bunch of little test tubes. This is an opportunity to potentially use material that would otherwise have been thrown away,” he said. (Photo copyright Harvard University.)

“Most lab experiments require equipment, like test tubes or 96-well assay plates,” said Whitesides, who was the study’s senior author. “But if you go out to smaller villages [in developing countries], these things are just not available.”

Since one glass test tube can cost as much as $5 while a square-foot of Bubble Wrap costs merely pennies, plastic Bubble Wrap has the potential to offer numerous advantages for pathologists and clinical laboratory scientists in resource-limited regions.

“You can take out a roll of Bubble Wrap, and you have a bunch of little test tubes,” Whitesides told NPR. “This is an opportunity to potentially use material that would otherwise have been thrown away.”

Lab Equipment from Other Common Household Items

Backed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Whitesides’ team continues to make headway with its “adaptive use” studies, which explore ways to transform readily available and low-cost materials into diagnostic tools for the developing world. His team also has developed other systems based on “adaptive use” such as eggbeaters and CD players that work as centrifuges and paper-based water quality tests.

Michele Barry, M.D., FACP, Professor of Medicine, Stanford University, believes Whitesides’ inexpensive alternative to traditional laboratory test tubes has many potential applications, including using Bubble Wrap to store samples and test water for toxic metals, such as mercury, arsenic, and lead. (Photo copyright Stanford University School of Medicine.)

Whitesides explained his quest for low-cost diagnostic tools in a New Scientist article.

“We like the idea of using materials that are readily available and seeing how much we can do with them, going far beyond their intended purpose and adapting them to address local problems,” he said.

Michele Barry, M.D., FACP, a Professor of Medicine at Stanford University, believes this latest research has many potential applications, including using Bubble Wrap to store samples and test water for toxic metals, such as mercury, arsenic, and lead.

“I had no idea that the bubbles themselves were sterile, which is fabulous,” she stated in the Goats and Soda article. “I just assumed it would be colonized by bugs. So, this is amazingly interesting.”

Ali Yetisen, Ph.D., a Postdoctoral Scholar at Harvard Medical School and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, offered a mixed assessment of Bubble Wrap’s potential as a replacement for traditional laboratory test tubes and petri dishes in a Chemistry World article.

Yetisen calls the work a good example of material adaptation, highlighting the wide range of roles that bubbles can fulfill. However, he points out that some automated diagnostic devices already use them to store liquids, and adds that the need to use syringes and then reseal could be a weakness.

Whitesides admits using Bubble Wrap to store liquid samples and perform analytical assays has some “obvious limitations,” including the fact the tiny test tubes can easily be popped, but he told Chemistry World, “We believe that these problems can be solved.”

Whitesides told NPR he hopes his proof-of-concept study will encourage other scientists to package the idea into a finished product.

—Andrea Downing Peck

Related Information:

Bubble Wrap Could Send Lab Costs Packing

Adaptive Use of Bubble Wrap for Storing Liquid Samples and Performing Analytical Assays

Don’t Pop That Bubble Wrap: Scientists Turn Trash Into Test Tubes