Researchers demonstrate that the length of blood telomeres may follow a specific pattern before cancer is detectable, which could lead to new diagnostic tests for detecting cancer in its early stages

Pathologists and Clinical pathology laboratories could soon have another tool to aid in the early detection of cancer. New research findings indicate that telomeres could serve as biomarkers for cancer if the right testing is done at the right times.

This study was conducted by Northwestern Medicine, (a collaboration between Northwestern Memorial HealthCare and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine) and Harvard University. It was titled “Blood Telomere Length Attrition and Cancer Development in the Normative Aging Study Cohort”. The findings bring scientists a step closer to understanding how telomeres change with the onset of cancer.

Predictive Biomarker for Cancer Might Be Used in Clinical Lab Testing

“Understanding this pattern of telomere growth may mean it can be a predictive biomarker for cancer,” said Lifang Hou, MD, PhD, the study’s lead author and a professor of preventive medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in a Northwestern Medicine news release. “Because we saw a strong relationship in the pattern across a wide variety of cancers, with the right testing these procedures could be used to eventually diagnose a wide variety of cancers.”

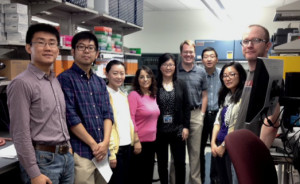

Lifang Hou, MD, PhD (center in black) with her research team at the Hou Lab, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. The over-arching research focus of the Hou Lab is to understand the biological mechanisms linking environmental and lifestyle factors with subclinical or clinical disease development, which ultimately lead to development of effective strategies for early detection and prevention of cancer and chronic diseases. (Photo and caption copyright: Northwestern University.)

Study Could Explain Why Early Hypotheses Yielded Inconsistent Results

Telomeres are often described as acting like the caps at the ends of shoelaces. They protect the ends of DNA. Each time a cell divides, telomeres get shorter. An older person will have shorter telomeres than a younger person.

Scientists have considered many hypotheses regarding how telomeres would behave in a person with cancer. The early theory was that the telomeres would be shorter. However, research to confirm that theory has yielded inconsistent results. In some studies, the length of telomeres in cancer patients was longer than expected, while in others it was shorter.

The recent Northwestern Medicine/Harvard study could explain the inconsistencies. The researchers followed a group of people over a 13-year period. They found that telomeres behave differently in a person who develops cancer a number of years before the disease is otherwise detectable.

The study involved 792 men participating in the Normative Aging Study (NAS). The study was established by the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs in 1963. All of the participants were healthy, male veterans at the outset of the study. They were contacted for clinical examinations every 3-5 years. Beginning in 1999, those exams included a blood sample for DNA analysis.

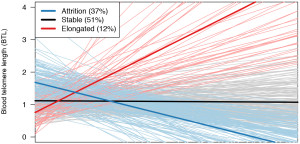

The image above is a spaghetti plot of individual participants’ blood telomere length (BTL) trajectory across the study. Participants were male, with mean age of 72 at baseline (range 55–100), and mostly white (535/579 or 95.5%). BTL decreased over time among participants free of cancer at baseline: from mean BTL of 1.26 ± 0.48 units at baseline to 0.86 ± 0.25 units at the fourth visit. The Northwestern Medicine/Harvard researchers found no significant associations between BTL and prevalent cancers. (Image and caption copyright: The authors and Elsevier B.V.)

Researchers Uncover a Pattern in Telomeres

For the telomere study, participants completed questionnaires and researchers reviewed their medical records to identify information about cancer diagnosis. Of the 792 participants, 213 were diagnosed with cancer. When the researchers examined the blood telomere length over time, a pattern began to emerge.

It appeared that the telomeres of people with cancer experience “a rapid shortening followed by a stabilization three to four years before cancer is diagnosed,” noted the press release issued by Northwestern. Previous studies had inconsistent results because they measured telomere length at different points in this newly discovered pattern.

Promising Results That Should Be Interpreted with ‘Caution’ Warn Researchers

All studies have limitations. In this case, all of the participants were male and mostly Caucasian. Also, the sample size limited the researchers’ ability “to analyze specific cancer subtypes other than prostate cancer,” leading them to conclude that “caution should be exercised in interpreting our results as different cancer subtypes have different biological mechanisms.”

Future studies are warranted, including studies designed to follow women and people of various ethnic backgrounds, as well as those designed to investigate how telomeres behave over time in people with different types of cancer. Some scientists believe that it could become standard for clinical laboratories to perform blood tests at regular intervals throughout a person’s life in order to detect cancer well before the disease actually begins.

—Dava Stewart

Related Information:

Blood Telomere Length Attrition and Cancer Development in the Normative Aging Study Cohort

Telomere Changes Predict Cancer

New Test Can Predict Cancer Up To 13 Years Before Disease Develops

Telomere Biomarker May Lead To Blood Test That Predicts Cancer Years in Advance

Harvard/Northwestern VA Study Claims To Predict Cancer Risk with Telomere Lengths