American Gut is using test results to create a microbiome database for use by researchers to better understand how microbes impact human health

Have you ever wondered what lurks in the dark corridors of your bowels? Now you can find out. Two entrepreneurial organizations—one a not-for-profit and the other a new clinical lab company—are charting new medical laboratory territory with the offer of an inexpensive poop test that reveals the type of microbes residing in your gut.

Where to Get Your Gut Microbes Analyzed

The not-for-profit organization American Gut, or British Gut in the United Kingdom (UK), which launched as crowd-funding projects on FundRazr, involve a private research project called the Human Food Project (HFP), which was initiated to compare the microbiomes of populations around the world. The Human Food Project is seeking a better understanding of modern disease by studying the coevolution of humans and their microbes.

People who pay American Gut’s $99 test fee (£75 for the UK project) receive a test kit to collect a stool sample to mail back for DNA sequencing. The test results will be provided to participants, but also benefit microbiome research.

The for-profit company is San Francisco-based uBiome, a DNA sequencing lab that offers three biome test kits:

1. A gut kit for $89,

2. A two-site kit, which includes the gut and choice of the mouth, nose, skin or genitals for $159, and,

3. A kit that includes all five sites for $399.

The company offers consumers an opportunity to compare their results with the biomes of people who are vegans, on a Paleo diet, overweight, heavy drinkers, and who monitor their own biomes over time for dietary and lifestyle changes.

American Gut Project Will Benefit Microbiome Research

Meanwhile, the American Gut project also aims to further scientific understanding of the diversity of the human microbial ecosystems and the impact of micro-organisms on the health of human populations globally, according to co-founders Rob Knight, Ph.D., a Professor at the University of Colorado Boulder and leading researcher at the BioFrontiers Institute, and HFP founder and anthropologist Jeff Leach, Ph.D..

American Gut co-founder Jeff Leach, Ph.D., an anthropologist and founder of the Human Food Project, has traveled worldwide seeking information on the coevolution of humans and their microbes, which, he believes, is the key to understanding modern disease. (Photo copyright Eating Well.)

Knight, whose lab group runs the American Gut Project, noted in a University of California Davis (UC Davis) press release that this “open source” project “truly brings together a dream team of microbiome investigators” and is building a framework for sharing information critical to understanding the microbiome.

“The ability to now inexpensively track the billions of microbes in each person’s gut is a watershed moment with profound implications toward how diets can improve human health,” said David Mills, Ph.D., a food science and technology professor at UC Davis. Mills, who is leading a Gates Foundation Grant effort to explore how milk components can reduce devastating diarrhea in at-risk children in developing countries, joined the American Gut Project along with colleague Bruce German, Ph.D., a food chemistry professor, with the goal of comparing the biome resulting from a Western diet with those of other peoples of the world.

Accuracy of Microbiome Tests in Question

It appears, however, that accuracy in the direct-to-consumer microbiome test market is still evolving. Tina Hesman Saey authored a “Glory Details” guest column about her own microbiome test results for Science News.

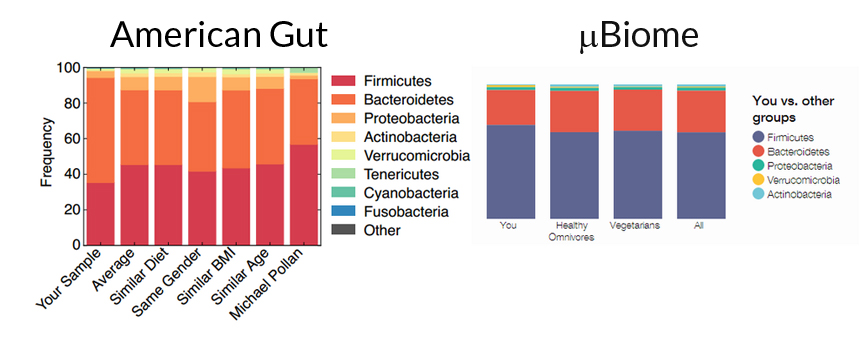

Saey says she had both services sequence her poop, but the test results didn’t match. “In fact,” she said, “they were almost complete opposites of each other in regard to the proportion of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes that make up my fecal microbiome.”

Pictured are the results of Tina Hesman Saey’s poop test from both microbiome testing services, which, according to Saey, do not match. These results, she says, demonstrate the lack of consistency and accuracy in microbiome testing that is confounding researchers and demonstrating the need for a test standard. (Image copyright Science News.)

To get to the bottom of this poop mystery, Saey asked Knight and uBiome co-founder and CEO Jessica Richman to explain what happened. They both offered various possible reasons for the discrepancies, ranging from the DNA extraction technique to the computer software used to analyze the DNA.

“All sorts of unlikely things are possible, and finding out which is true is difficult,” said Knight, who is working with other scientists to create consistency in test results.

The lack of study reproducibility apparently is a source of frustration for all scientists using biome information in their work. “To me it seemed like cowboy country,” Rashmi Sinha, Ph.D., an epidemiologist at the National Cancer Institute, told Saey. “It needed to have some kind of order,” she added.

Researchers Tackle Inconsistency in Microbiome Testing

To provide consistency in testing, Sinha, along with Knight and 14 microbiome labs, established the Microbiome Quality Control project (MBQC). Labs participating in the MBQC project are analyzing a variety of fecal samples to see if they all come up with similar results as to what’s in them.

Sinha is working with Emma Allen-Vercoe, Ph.D., a molecular biologist and associate professor at Ontario, Canada’s University of Guelph to create “robo-gut”. This is an artificial colon that cooks up a liter of feces at a time, to provide a test standard for microbiome researchers.

Microbes Cause Diseases but Essential to Human Survival

While American Gut and uBiome lab are pioneering what may be a new market for this menu of clinical laboratory tests, the launch of the Common Fund Human Microbiome Project (HMP)—a consortium of researchers from nearly 80 universities and scientific research facilities led by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—opened the door to an explosion in microbiome research that is likely to generate new diagnostic tests. (See Dark Daily, “Expanding Knowledge About the Human Microbiome Will Lead to New Clinical Pathology Laboratory Tests,” July 7, 2010)

Studies have linked human microbes to a myriad of health conditions, noted a report from the University of Utah, including acne, antibiotic-related diarrhea, asthma/allergies, autism, autoimmune diseases, various cancers, dental cavities, depression and anxiety, diabetes, eczema, gastric ulcers, atherosclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, malnutrition, and obesity.

HMP researchers also report that humans cannot survive without their microbes. Bacteria genes aid in human digestion and absorption of nutrients that otherwise would be unavailable, pointed out Lita Proctor, Ph.D., HMP program manager at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) in a NHGRI press release.

“Microbes in the gut break down many of the proteins, lipids and carbohydrates in our diet into nutrients that we can then absorb,” she explained, noting that these microbes also produce beneficial compounds, like vitamins and anti-inflammatories that our genome cannot produce—some of which are anti-inflammatories that regulate some immune system responses to disease, such as swelling.

As the information above demonstrates, the art and science of DNA sequencing and how these sequences are analyzed still falls short of the gold standard of accuracy needed to use such assays for clinical purposes. For this reason, it is not likely that clinical laboratory professionals and pathologists will soon have FDA-cleared assays that can be used in clinical care.

—Patricia Kirk

Related Information:

Here’s the Poop on Getting Your Gut Microbiome Analyzed

Microbiome: Your Body Houses 10x More Bacteria than Cells

How Good Gut Bacteria Could Transform Your Health

The Bacterial Zoo In Your Bowel

NIH Human Microbiome Project Defines Normal Bacterial Makeup of the Body

Expanding Knowledge about the Human Microbiome Will Lead to New Clinical Pathology Laboratory Tests