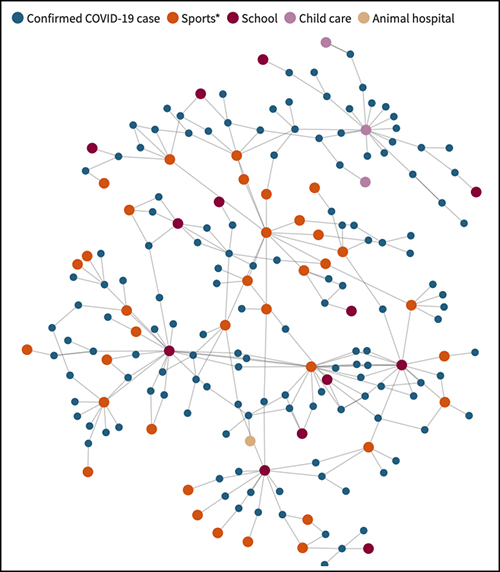

Data was used to create a transmission map that tracked the spread of infections among school athletes and helped public health officials determine where best to disrupt exposure

Genomic sequencing played a major role in tracking a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in a Minnesota school system. Understanding how and where the coronavirus was spreading helped local officials implement restrictions to help keep the public safe. This episode demonstrates how clinical laboratories that can quickly sequence SARS-CoV-2 accurately and at a reasonable cost will give public health officials new tools to manage the COVID-19 pandemic.

Officials in Carver County, Minn., used the power of genomic epidemiology to map the COVID-19 outbreak, and, according to the Star Tribune, revealed how the B.1.1.7 variant of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus was spreading through their community.

“The resulting investigation of the Carver County outbreak produced one of the most detailed maps of COVID-19 transmission in the yearlong history of the pandemic—a chart that looks like a fireworks grand finale with infections producing cascading clusters of more infections,” the Star Tribune reported.

Private Labs, Academic Labs, Public Health Labs Must Work Together

For gene sequencing to guide policy and decision making as well as it did in Carver County, coordination, cooperation, and standardization among public, private, and academic medical laboratories is required. Additionally, each institution must report the same information in similar formats for it to be the most useful.

In “Staying Ahead of the Variants: Policy Recommendations to Identify and Manage Current and Future Variants of Concern,” the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (JHCHS) at the Bloomberg School of Public Health lists recommendations for how to build a coordinated sequencing program.

Priority recommendations include:

- “Maintain Policies That Slow Transmission: Variants will continue to emerge as the pandemic unfolds, but the best chance of minimizing their frequency and impact will be to continue public health measures that reduce transmission. This includes mask mandates, social distancing requirements, and limited gatherings.

- “Prioritize Contact Tracing and Case Investigation for Data Collection: Cases of variants of concern should be prioritized for contact tracing and case investigation so that public health officials can observe how the new variant behaves compared to previously circulating versions.

- “Develop a Genomic Surveillance Strategy: To guide the public health response, maximize resources, and ensure an equitable distribution of benefits, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should develop a national strategy for genomic surveillance to implement and direct a robust SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance program, drawing on resources and expertise from across the US government.

- “Improve Coordination for Genomic Surveillance and Characterization: There are several factors in creating a successful genomic surveillance and characterization network. Clear leadership and coordination will be necessary.”

Practical Application of Genomic Sequencing

Genomic epidemiology uses the genetic sequence of a virus to better understand how and where a given virus is spreading, as well as how it may be mutating. Pathologists understand that this information can be used at multiple levels.

Locally, as was the case in Carver County, Minn., it helps school officials decide whether to halt sports for a time. Nationally, it helps scientists identify “hot spots” and locate mutations of the coronavirus. Using this data, vaccine manufacturers can adjust their vaccines or create boosters as needed.

Will Cost Decreases Provide Opportunities for Clinical Laboratories?

Every year since genomic sequencing became available the cost has decreased. Experts expect that trend to continue. However, as of now, the cost may still be a barrier to clinical laboratories that lack financial resources.

“Up-front costs are among the challenges that limit the use of genomic sequencing technologies,” wrote the federal Government Accountability Office (GAO) in “Gene Sequencing Can Track COVID Variants, But High Costs and Security and Privacy Concerns Present Challenges.”

“Purchasing laboratory equipment, computer resources, and staff training requires significant up-front investments. However, the cost per sequence is far less today than it was under earlier methods,” the GAO noted. This is good news for public and independent clinical laboratories. Like Carver County, a significant SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in the future may be averted thanks to genetic sequencing.

“The first piece of the cluster was spotted in a private K-8 school, which served as an incubator of sorts because its students live in different towns and play on different club teams,” the Star Tribune reported.

Finding such clusters may provide opportunities to halt the outbreak. “We can try to cut it off at the knees or maybe get ahead of it,” epidemiologist Susan Klammer with Minnesota Public Health and for childcare and schools, told the Star Tribune.

This story is a good example of how genomic sequencing and surveillance tracking—along with cooperation between public health agencies and clinical laboratories—are critical elements in slowing and eventually halting the spread of COVID-19.

—Dava Stewart

Related Information:

Mapping of Carver County Outbreak Unmasks How COVID Spreads

COVID Variants Are Like “a Thief Changing Clothes” and Our Camera System Barely Exists

Biden Administration Announces Actions to Expand COVID-19 Testing