Four International Pandemics That Occurred Prior to COVID-19 and Contributed to Increased Clinical Laboratory Testing to Aid in Managing the Outbreaks

Since 1900, millions have died worldwide from previous viruses that were as deadly as SARS-CoV-2. But how much do pathologists and clinical laboratory scientists know about them?

SARS-CoV-2 continues to infect populations worldwide. As of May 28, 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that 168,599,045 people have been diagnosed with COVID-19 infections globally, and 3,507,377 individuals have perished from the coronavirus.

At the same time, federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) statistics show there have been 33,018,965 cases of COVID-19 in the United States, 589,547 of which resulted in death.

But COVID-19 is just the latest in a string of pandemics that spread across the planet in the past century. Since 1900, there have been four major international pandemics resulting in millions of deaths. But how many people even remember them? And how many pathologists, microbiologists, and clinical laboratory scientists working today experienced even the most recent of these four global pandemics?

Here is a summary/review of these major pandemics to give clinical laboratory professionals context for comparing the COVID-19 pandemic to past pandemics.

Spanish Flu of 1918

The 1918 influenza pandemic, commonly referred to as the Spanish Flu, was the most severe and deadliest pandemic of the 20th century. This pandemic was caused by a novel strand of the H1N1 virus that had avian origins. It is estimated that approximately one third of the world’s population (at that time) became infected with the virus.

According to a CDC article, the flu pandemic of 1918 was responsible for at least 50 million deaths worldwide, with about 675,000 of those deaths occurring in the United States. This pandemic had an unusually high death rate among healthy individuals between the ages of 15 and 34 and actually lowered the average life expectancy in the United States by more than 12 years, according to a CDC report, titled, “The Deadliest Flu: The Complete Story of the Discovery and Reconstruction of the 1918 Pandemic Virus.”

Interestingly, experts feel the 1918 flu strain never fully left us, but simply weakened and became less lethal as it mutated and passed through humans and other animals.

Influenza expert and virologist, Jeffery Taubenberger, MD, PhD, Chief, Viral Pathogenesis and Evolution Section at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), believes that the lingering descendants of the 1918 influenza virus are still contributing to flu pandemics occurring today.

“All those pandemics that have happened since—1957, 1968, 2009—all those pandemics are derivatives of the 1918 flu,” he told The Washington Post. “The flu viruses that people get this year, or last year, are all still directly related to the 1918 ancestor.”

1957 Asian Flu

The H2N2 virus, which caused the Asian Flu, first emerged in East Asia in February 1957 and quickly spread to other countries throughout Asia. The virus reached the shores of the US by the summer of 1957, where the number of infections continued to rise, especially among the elderly, children, and pregnant women.

According to the CDC, “this H2N2 virus was comprised of three different genes from an H2N2 virus that originated from an avian influenza A virus, including the H2 hemagglutinin and the N2 neuraminidase genes.”

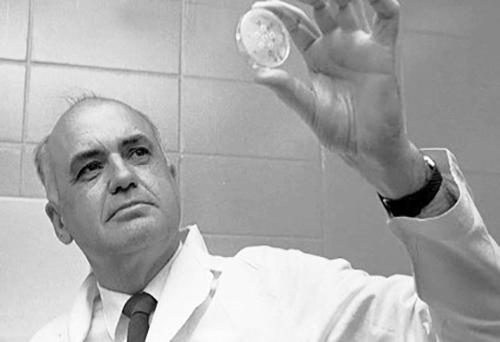

Between 1957-1958, the Asian Flu spread across the planet causing between one to two million deaths, including 116,000 deaths in the US alone. However, this pandemic could have been much worse were it not for the efforts of microbiologist and vaccinologist Maurice Hilleman, PhD, who in 1958 was Chief of the Department of Virus Diseases at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

Concerned that the Asian flu would wreak havoc on the US, Hilleman—who today is considered the father of modern vaccines—researched and created a vaccine for it in four months. Public health experts estimated the number of US deaths could have reached over one million without the fast arrival of the vaccine, noted Scientific American, adding that though Hilleman “is little remembered today, he also helped develop nine of the 14 children’s vaccines that are now recommended.”

1968 Hong Kong Flu

The 1968 influenza pandemic known as the Hong Kong flu emerged in China and persisted for several years. Within weeks of its emergence in the heavily populated Hong Kong, the flu had infected more than 500,000 people. Within months, the highly contagious virus had gone global.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, this pandemic was initiated by the influenza A subtype H3N2 virus and is suspected to have evolved from the viral strain that caused the 1957 flu pandemic through a process called antigenic shift. In this case, the hemagglutinin (H) antigen located on the outer surface of the virus underwent a genetic mutation to manufacture the new H3 antigen. Persons who had been exposed to the 1957 flu virus seemed to retain immune protection against the 1968 virus, which, Britannica noted, could help explain the relative mildness of the 1968 outbreak.

It is estimated that the 1968 Hong Kong Flu killed one to four million people worldwide, with approximately 100,000 of those deaths occurring in the US. A vaccine for the virus was available by the end of 1968 and the outbreaks appeared to be under control the following year. The H3N2 virus continues to circulate worldwide as a seasonal influenza A virus.

2009 H1N1 Swine Flu

In the spring of 2009, the novel H1N1 influenza virus that caused the Swine Flu pandemic was first detected in California. It soon spread across the US and the world. This new H1N1 virus contained a unique combination of influenza genes not previously identified in animals or people. By the time the World Health Organization (WHO) declared this flu to be a pandemic in June of 2009, a total of 74 countries and territories had reported confirmed cases of the disease. The CDC estimated there were 60.8 million cases of Swine Flu infections in the US between April 2009 and April 2010 that resulted in approximately 274,304 hospitalizations and 12,469 deaths.

This pandemic primarily affected children and young and middle-aged adults and was less severe than previous pandemics. Nevertheless, the H1N1 pandemic dramatically increased clinical laboratory test volumes, as Dark Daily’s sister publication, The Dark Report, covered in “Influenza A/H1N1 Outbreak Offers Lessons for Labs,” TDR June 8, 2009.

“Laboratories in the United States experienced a phenomenal surge in specimen volume during the first few weeks of the outbreak of A/H1N1. This event shows that the capacity in our nation’s public health system for large amounts of testing is inadequate,” Steven B. Kleiboeker, DVM, PhD, told The Dark Report. At that time Kleiboeker was Chief Scientific Officer and a Vice-President of ViraCor Laboratories in Lee’s Summit, Mo.

1.7 Million ‘Undiscovered’ Viruses

As people travel more frequently between countries, it is unlikely that COVID-19 will be the last pandemic that we encounter. According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), there are 1.7 million “undiscovered” viruses that exist in mammals and birds and approximately 827,000 of those viruses have the ability to infect humans.

Thus, it remains the job of pathologists and clinical laboratories worldwide to remain ever vigilant and prepared for the next global pandemic.

—JP Schlingman

Related Information:

The History of Influenza Pandemics by the Numbers

The Deadliest Flu: The Complete Story of the Discovery and Reconstruction of the 1918 Pandemic Virus

‘The 1918 Flu is Still With Us’: The Deadliest Pandemic Ever is Still Causing Problems Today

The Man Who Beat the 1957 Flu Pandemic

2009 H1N1 Pandemic (H1N1pdm09 virus)

This Is How We Prevent Future Pandemics, Say 22 Leading Scientists