AccuWeather interviewed experts, including pathologists who have analyzed the virus, who say SARS-CoV-2 is susceptible to heat, light, and humidity, while others study weather patterns for their predictions

AccuWeather, as it watched the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, wanted to know what effect that warmer spring temperatures might have on curbing the spread of the virus. There is a good reason to ask this question. As microbiologists, infectious disease doctors, and primary care physicians know, the typical start and end to every flu season is well-documented and closely watched.

As SARS-CoV-2 ravages countries around the world, clinical pathologists and microbiologists debate whether it will subside as temperatures rise in Spring and Summer. Recent analyses suggest it may indeed be a seasonal phenomenon. However, some infectious disease specialists have expressed skepticism.

In a private conference call with investment analysts that was later leaked on social media, John Nicholls, MBBS, FRCPA, FHKCPath, FHKAM, Clinical Professor in the University of Hong Kong Department of Pathology, said there are “Three things the virus does not like: 1. sunlight 2. temperature and 3. humidity,” AccuWeather reported.

CNN reported that Nicholls was part of a research team which reproduced the virus in January to study its behavior and evaluate diagnostic tests. Nicholls was also involved in an early effort to analyze the coronavirus associated with the 2003 SARS outbreak involving SARS-CoV, another coronavirus that originated in Asia.

“Sunlight will cut the virus’ ability to grow in half, so the half-life will be 2.5 minutes and in the dark it’s about 13 to 20,” Nicholls told AccuWeather. “Sunlight is really good at killing viruses.” And that, “In cold environments, there is longer virus survival than warm ones.” He added, “I think it will burn itself out in about six months.”

Can Weather Predict the Spread of COVID-19?

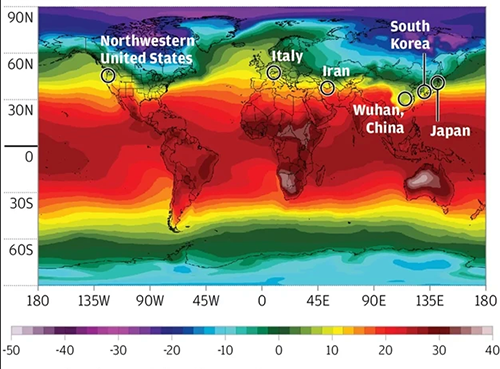

Other researchers have analyzed regional weather data to see if there’s a correlation with incidence of COVID-19. A team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) found that the number of cases has been relatively low in areas with warm, humid conditions and higher in more northerly regions. They published their findings in SSRN (formerly Social Science Research Network), an open-access journal and repository for early-stage research, titled “Will Coronavirus Pandemic Diminish by Summer?”

FREE Webinar | What Hospital and Health System Labs Need to Know

About Operational Support and Logistics During the COVID-19 Outbreak

Wednesday, April 1, 2020 @ 1PM EDT — Register or Stream now

The MIT researchers found that as of March 22, 90% of the transmissions of SARS-CoV-2 occurred within a temperature range of three to 17 degrees Celsius (37.4 to 62.6 degrees Fahrenheit) and an absolute humidity range of four to nine grams per cubic meter. Fewer than 6% of the transmissions have been in warmer climates further south, they wrote.

“Based on the current data on the spread of [SARS-CoV-2], we hypothesize that the lower number of cases in tropical countries might be due to warm humid conditions, under which the spread of the virus might be slower as has been observed for other viruses,” they wrote.

In the US, “the outbreak also shows a north-south divide,” with higher incidence in northern states, they wrote. The outliers are Oregon, with fewer than 200 cases, and Louisiana, where, as of March 22, approximately 1,000 had been reported.

There’s been a recent spike in reported cases from warmer regions in Asia, South America, and Africa, but the MIT researchers attribute this largely to increased testing.

Still, “there may be several caveats to our work,” they wrote in their published study. For example, South Korea has been engaged in widespread testing that includes asymptomatic individuals, whereas other countries, including the US, have limited testing to a narrower range of people, which could mean that more cases are going undetected. “Further, the rate of outdoor transmission versus indoor and direct versus indirect transmission are also not well understood and environmental related impacts are mostly applicable to outdoor transmissions,” the MIT researchers wrote.

Even in warmer, more humid regions, they advocate “proper quarantine measures” to limit the spread of the virus.

The New York Times (NYT) reported that other recent studies have shown a correlation between weather conditions and the incidence of COVID-19 outbreaks as well, though none of this research has been peer reviewed.

Why the Correlation? It’s Unclear, MIT Says

Though the MIT researchers found a strong relation between the number of cases and weather conditions, “the underlying reasoning behind this relationship is still not clear,” they wrote. “Similarly, we do not know which environmental factor is more important. It could be that either temperature or absolute humidity is more important, or both may be equally or not important at all in the transmission of [SARS-CoV-2].”

Some experts have looked at older coronaviruses for clues. “The coronavirus is surrounded by a lipid layer, in other words, a layer of fat,” said molecular virologist Thomas Pietschmann, PhD, Director of the Department for Experimental Virology at the Helmholtz Center for Infection Research in Hanover, Germany, in a story from German news service Deutsche Welle. This makes it susceptible to temperature increases, he suggested.

However, Pietschmann cautioned that because it’s a new virus, scientists cannot say if it will behave like older viruses. “Honestly speaking, we do not know the virus yet,” he concluded.

Marc Lipsitch, DPhil, Professor of Epidemiology and Director of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, is skeptical that warmer weather will put the brakes on COVID-19. “While we may expect modest declines in the contagiousness of SARS-CoV-2 in warmer, wetter weather, and perhaps with the closing of schools in temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, it is not reasonable to expect these declines alone to slow transmission enough to make a big dent,” he wrote in a commentary for the center.

How should pathologists and clinical laboratories in this country prepare for COVID-19? Lipsitch wrote that Influenza does tend to be seasonal, in part because cold, dry air is highly conducive to flu transmission. However, “for coronaviruses, the relevance of this factor is unknown.” And “new viruses have a temporary but important advantage—few or no individuals in the population are immune to them,” which means they are not as susceptible to the factors that constrain older viruses in warmer, more humid months.

So, we may not yet know enough to adequately prepare for what’s coming. Nevertheless, monitoring the rapidly changing data on COVID-19 should be part of every lab’s daily agenda.

—Stephen Beale

Related Information:

What Could Warming Mean for Pathogens like Coronavirus?

Seasonality of SARS-CoV-2: Will COVID-19 Go Away on Its Own in Warmer Weather?

Temperature, Humidity and Latitude Analysis to Predict Potential Spread and Seasonality for COVID-19

Warmer Weather May Slow, but Not Halt, Coronavirus

Higher Temperatures Affect Survival of New Coronavirus, Pathologist Says

Will Coronavirus Pandemic Diminish by Summer?

Will Warm Weather Really Kill Off Covid-19?

Will Warmer Weather Stop the Spread of the Coronavirus?

Why Do Dozens of Diseases Wax and Wane with the Seasons—and Will COVID-19? Seasonality Of SARS-Cov-2: Will COVID-19 Go Away on Its Own in Warmer Weather?